Faculty impact: Helping families recover from homelessness

When Laura Gultekin moved to Ann Arbor for a new job at Michigan Medicine’s C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital, she saw how severe gaps in health, known as health disparities, can be among different populations throughout the county. Her nursing career began in a Washington, D.C. pediatric intensive care unit (ICU), which served children from disadvantaged communities.

“We had children coming to the ICU every day with conditions that are normally manageable, like diabetes and asthma,” Gultekin explained. “I thought that was the norm.”

Gultekin saw a significant difference in Ann Arbor.

“I saw asthmatics and kids with diabetes maybe once a month and they rarely had complex social issues,” she said. “They existed, but they weren’t as severe compared to D.C. It was a real eye-opener.”

The catalyst

The realization prompted Gultekin to enroll at the University of Michigan School of Nursing to earn her Family Nurse Practitioner master’s degree. She found an ideal opportunity to learn about health disparities and how to prevent them on a project with UMSN Professor Barbara Brush.

“We were working with families in unstable housing situations and looking at resources for kids,” she said. “The project involved talking to the women to understand what was happening in their lives. That sparked a real interest for me.”

“We were working with families in unstable housing situations and looking at resources for kids,” she said. “The project involved talking to the women to understand what was happening in their lives. That sparked a real interest for me.”

Gultekin developed such a strong commitment to the families that she went on to earn her Ph.D. at UMSN and become an assistant professor as a means to develop new research and interventions aimed at helping families prevent and recover from homelessness.

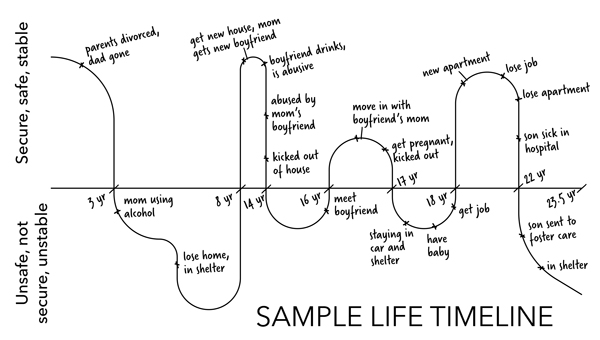

She is currently working on a project called the Clinical Ethnographic Narrative Intervention. It’s a patient-centered method to help women experiencing homelessness to understand how their experiences, choices and external factors have impacted their current situation. The women are given a safe space to tell Gultekin and her team the stories of their lives, often going back to childhood. The researchers organize the stories into a narrative, then the women continue the process by making a graph of their life experiences.

“They draw it out so they can see the ups and downs,” said Gultekin. “We ask them about how they got to the good and bad points so they can reflect on some of the cycles such as bad relationships. It’s also really important for them to recognize the moments they have been able to move forward.”

The experience is often empowering for the women. Many share stories they haven’t told anyone else.

“There is a sense of safety communicating with nurses,” she said. “The women are given a voice and they realize they’ve been through so much.”

That role of the nurse as an advocate fits with Gultekin’s view of nursing as a whole.

“Nursing, at its heart, is about all aspects of a person’s life,” she said. “We have a really holistic view that includes environment. My view started there but expanded to really understand the entire context of homelessness. Homelessness is an extreme of a negative environment.”

The child’s experience

Gultekin is part of UMSN’s research group CASCAID (Complex ACEs [adverse childhood experiences] Complex Aid), which focuses on how negative life events can impact health in childhood and beyond.

“We can no longer ignore that adverse experiences need to be addressed in health care,” she said. “The toxic stress of instability can be life shortening.”

“We can no longer ignore that adverse experiences need to be addressed in health care,” she said. “The toxic stress of instability can be life shortening.”

Gultekin’s work addresses the cycles of homelessness that hit multiple generations.

“We often find that these women experienced homelessness as children and now their children are experiencing it,” she said. “The mothers want to protect them but they don’t always understand how their experiences affect their children. That’s why it’s not enough to put a roof over someone’s head. We need to look deeper.”

Another component of CASCAID’s work that is important to Gultekin is the care of nurses who work with vulnerable populations.

“We see and hear a lot of terrible things,” she said. “It can re-active our own traumas so it’s important to practice self-care.”

Despite the disquiet that comes from these often emotionally raw encounters, Gultekin says it’s imperative to continue the hands-on work.

“I need to keep a foot in the real world to know that I’m not conducting research that is disconnected from the people I’m trying to help,” she said.

Making the most of the data

Gultekin is able to devote a significant amount of time to her research because she holds a named professorship as the Suzanne Bellinger Feetham Professor of Nursing. She teaches classes during one semester and uses the professorship to have a full semester dedicated to her research.

Gultekin is able to devote a significant amount of time to her research because she holds a named professorship as the Suzanne Bellinger Feetham Professor of Nursing. She teaches classes during one semester and uses the professorship to have a full semester dedicated to her research.

“It’s incredibly valuable to have that time,” she said. “I really like the time I’m able to dig through the data and talk with the research team. We have different voices at the table and that adds perspective.”

Moving forward

Gultekin is hopeful her work will build the understanding of homelessness.

“There’s a lot of thought that homelessness is simply related to poverty and not having jobs,” she explained. “The reality is that it’s most often the intersection of many traumatic events. It’s often about domestic violence, childhood maltreatment, and never having been given the same tools that many of us have to build a stable life.”

Despite the obstacles, Gultekin is adamant that with the right resources and support, the overwhelming majority of people experiencing homelessness have the ability to recover.

“They’ve all got these stories of incredible resilience that don’t get recognized,” she explained. “Recognizing their own agency and helping them harness that to move themselves forward is my goal.”